Breaking Down The News: Water as a Weapon – How India Plans to Squeeze Pakistan’s Lifeline

In the aftermath of the brutal terrorist attack in Pahalgam that claimed the lives of 26 civilians, India has taken an unprecedented step by suspending the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan. Signed in 1960 and brokered by the World Bank, the treaty had long been considered a symbol of cooperation, surviving even the wars between the two nations. However, the recent developments indicate that water is no longer just a resource—it is now emerging as a strategic weapon. India’s suspension of the treaty signals a major escalation in the geopolitical dynamics of South Asia, raising critical questions about the future of river flows, water security, and regional stability.

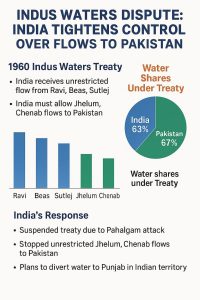

The Indus Waters Treaty had clearly divided the six rivers of the Indus basin between the two countries. The three western rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab—were allocated to Pakistan with a commitment from India to allow their uninterrupted flow. Meanwhile, India was granted rights over the three eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej. Although India could use the western rivers for limited purposes like hydroelectric power generation and irrigation, it could not store or divert large volumes of water. This heavily tilted the arrangement in Pakistan’s favor, granting it access to nearly 80 percent of the basin’s water. That arrangement now lies in suspension, following India’s declaration that it would reconsider all previous obligations until Pakistan demonstrates seriousness about ending cross-border terrorism.

Immediately after suspending the treaty, India laid out a three-phase plan to exert pressure on Pakistan by controlling the flow of waters. In the short term, the government has begun desilting operations to enhance water storage capacity within Indian territory. It has also ceased sharing hydrological data with Pakistan, a move that strips Islamabad of critical information needed for water management. In the medium term, India is fast-tracking the construction of strategic dams such as the Shahpurkandi Dam and the Ujh Multipurpose Project. In the long term, India plans to explore major diversion schemes that could significantly alter the flow patterns of the rivers feeding Pakistan.

The diverted waters will primarily benefit Indian states that lie close to the Indus basin. Punjab and Jammu & Kashmir stand to gain the most, with projects like the Shahpurkandi Dam already completed and capable of supporting both irrigation and hydroelectric production. Rajasthan will benefit through enhancements to the Indira Gandhi Canal system, ensuring that more water reaches its arid regions. Haryana is another intended beneficiary through the Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal, although political disputes have stalled its completion. Uttar Pradesh is part of future plans involving large-scale trans-basin diversions, a vision that will take shape only after substantial infrastructure development over the next decade.

Progress on these projects varies considerably. The Shahpurkandi Dam is already complete and undergoing capacity testing, ready to divert significant volumes of the Ravi’s waters back into Indian fields. The Ujh Multipurpose Project has received all necessary clearances but awaits the start of physical construction. Meanwhile, the Indira Gandhi Canal is fully operational but is currently being upgraded to handle higher volumes of water. The Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal remains a political flashpoint between Punjab and Haryana, with Punjab resisting its completion on grounds of water scarcity. Large trans-basin diversions to states like Uttar Pradesh are in the planning stage and are expected to take at least another decade to materialize.

Despite these ambitious plans, India faces significant technical and geographical constraints. While India has suspended its treaty obligations, it does not yet possess enough storage capacity on the western rivers to hold back all the water that would naturally flow into Pakistan. Massive rivers like the Indus and the Chenab carry volumes far beyond what current Indian reservoirs can handle. Without enough dam storage, excess monsoon water would inevitably have to be released, or else Indian territories themselves would face catastrophic flooding. Therefore, while India can meaningfully restrict water flows during dry seasons, it must still release surplus water during the wet months, at least until larger infrastructure projects are completed.

Realistically, India’s timeline for significantly squeezing Pakistan’s water lifeline will unfold over years, not months. In the short term, during 2025 and 2026, India can impose some restrictions, especially during the winter and summer dry seasons. By 2027 to 2030, with projects like Shahpurkandi, Ujh, and further canal expansions fully operational, India could severely curtail flows during critical agricultural seasons in Pakistan. After 2030, if mega-projects like the Ladakh reservoirs and large trans-basin diversions are realized, Pakistan could see up to a 35–40 percent reduction in its current Indus system inflows.

The geopolitical consequences of these moves are immense. For Pakistan, already struggling with internal economic and political turmoil, any significant disruption of its water supply could push it toward further instability. For India, using water as a form of pressure sends a strong message but also carries the risk of international backlash if humanitarian crises emerge downstream. Global actors like China and the World Bank are likely to scrutinize the situation closely, given the enormous stakes involved in any alteration of transboundary river flows.

In conclusion, India’s move to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty is not just a symbolic act. It marks the beginning of a long-term strategy to reshape South Asia’s hydro-politics. While India cannot immediately stop all waters from flowing to Pakistan without hurting itself, it has created a powerful tool of leverage that could be fully operational over the next decade. Whether this new weapon reshapes negotiations, triggers future conflict, or forces a new era of water-sharing talks remains to be seen. One thing is clear: in the new great game between India and Pakistan, rivers are no longer neutral; they have become instruments of power.

According to Arun Durairajan, Research Partner at Statscope India, “The Indian government’s decision to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty could go down as one of the most strategically brilliant and bloodless wars in modern South Asian history. By controlling the flow of life-sustaining rivers, India is leveraging a non-violent, economically devastating tool that strikes at the heart of Pakistan’s agricultural and civic infrastructure. This is not a skirmish at the border—it’s a tectonic shift in asymmetrical warfare. Water is the new gold, and India is finally guarding its vault. The message is clear: terrorism has a cost, and it will be paid in scarcity.”

p.s This article has been written in consultation with the data science experts at www.statscope.in