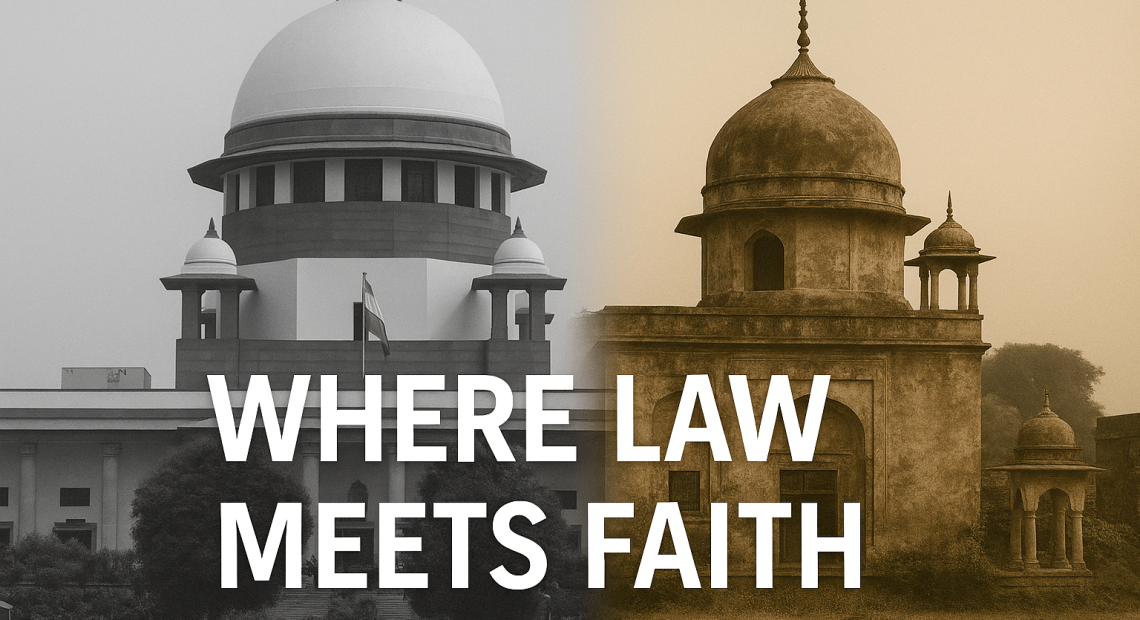

The Waqf Amendment Bill in Supreme Court: A Constitutional Challenge or Legal Course Correction?

The ongoing Supreme Court hearing on the Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2023, marks a critical legal moment where religious tradition, statutory reform, and constitutional rights intersect. At the heart of the petitions challenging the bill lies a singular contentious clause—the removal of the “Waqf by User” provision—which the petitioners argue infringes on the rights of religious communities under the Indian Constitution. While the rest of the bill is being seen largely as administrative and constitutionally safe, the deletion of this one provision has stirred anxieties over erasure of centuries-old religious practices.

The case gained additional complexity when Justice Sanjiv Khanna recused himself from the matter, prompting expectations that Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s successor, CJI Gavai, may choose to refer at least part of the bill—specifically the Waqf by User clause—to a Constitutional Bench. Legal experts largely believe the rest of the bill will continue to remain in force without a stay, signaling the Court’s attempt to strike a balance between governance reform and protection of fundamental religious freedoms.

The Core Controversy: Waqf by User and Article 26(b)

The “Waqf by User” doctrine has long been a unique feature of Indian waqf jurisprudence. It allowed religious properties—such as mosques, dargahs, graveyards, and shrines—that had been used informally for religious purposes over decades to be recognized as waqf, even in the absence of formal documentation or waqf deeds. This provision had particular significance in rural and undocumented settings, where communities often lacked the resources to formalize such spaces but maintained them across generations.

The 2023 amendment struck down this very foundation by removing the Explanation to Section 4(2), effectively denying waqf status to properties used religiously without registered title. The consequence is profound: centuries-old mosques or dargahs without formal land documents could now legally be classified as encroachments.

Petitioners argue this violates Article 26(b) of the Constitution, which guarantees every religious denomination the right to manage its own affairs in matters of religion. They assert that the state, by erasing the historical basis for recognizing these spaces, interferes with the autonomy of religious communities and fails to account for traditional forms of worship and religious organization that may not be codified on paper but exist in lived practice.

The Constitutional Tightrope: Articles at Play

While Article 26(b) is central to the petitions, other constitutional provisions come into indirect play. Article 25, which guarantees freedom of religion, may be affected if communities are unable to use spaces they have considered sacred for generations. Article 300A—a constitutional right introduced after the removal of the fundamental right to property—may also be in question, as the denial of waqf status to user-based claims could lead to loss of religious property without due legal process.

Even Article 14, which ensures equality before the law, is touched upon, as the original Waqf Act provided Waqf Boards with broad powers that critics allege enabled arbitrary land claims without recourse to civil courts. However, with the 2023 amendment narrowing waqf recognition, the focus has now shifted to whether this narrowing process itself violates the rights of the religious communities it aims to regulate.

What Remains Unchallenged: The Safe Amendments

Legal scholars broadly agree that most of the other amendments in the Waqf Bill fall within the realm of legitimate governance and are unlikely to face constitutional hurdles. These include:

Mandatory digitization of all waqf property records by the Central Waqf Council.

Time-bound waqf property surveys to prevent land misuse or encroachment.

Reinforcement of the bar on alienation (sale, gift, mortgage) of waqf properties without government approval.

Clarification of Waqf Board appointments, eligibility, and powers of supersession by state governments.

Retention of exclusive Waqf Tribunal jurisdiction, barring civil court interference in waqf-related disputes.

Increased penalties for encroachment, aimed at protecting religious endowments from illegal occupation.

These provisions aim to streamline waqf administration and prevent misuse or fraudulent claims. As they do not interfere with fundamental religious rights or established judicial principles, they are expected to pass constitutional muster.

Judicial Dynamics: From CJI Khanna’s Recusal to CJI Gavai’s Probable Referral

In a recent development, Justice Sanjiv Khanna—who was slated to hear the matter—recused himself, creating anticipation around how the new Chief Justice of India, D.Y. Chandrachud’s successor CJI Gavai, will handle the sensitive petition. According to legal sources, it is highly likely that CJI Gavai will refer the matter—at least the “Waqf by User” clause—to a five-judge Constitutional Bench for detailed scrutiny. The rest of the bill, which pertains mostly to administrative reforms, is expected to be allowed to remain operational.

This partial referral strategy would enable the Court to continue ongoing waqf reforms while separately examining the one contentious area that deals with potential constitutional rights violations.

The Likely Outcome: Partial Referral, Partial Clearance

Based on expert assessments, the Supreme Court seems poised to carve the bill into two parts—sending the “Waqf by User” provision for constitutional evaluation while letting the rest take effect as law. This approach would reduce administrative limbo and help Waqf Boards begin digitization, land recovery, and governance improvements, while still safeguarding constitutional scrutiny on the most sensitive religious liberty question.

Legal observers point out that this pragmatic approach mirrors the Court’s recent trend: surgical judicial review, rather than wholesale rejection or endorsement of complex laws.

Conclusion: A Test of Constitutional Faith and Federal Prudence

The Waqf Amendment Bill presents an acid test for India’s constitutional ethos—how far can the state modernize religious endowment law without infringing upon the spirit and practice of faith? The Court now finds itself balancing legal precision with the historical and emotional weight of undocumented worship sites.

If the “Waqf by User” doctrine is permanently struck down, it may redefine how India recognizes religious heritage outside formal law. If upheld, it may reaffirm the pluralistic tradition of lived faiths shaping land rights. Either way, what unfolds in the Courtroom will resonate beyond lawbooks—into graveyards, mosques, and the memory of generations.