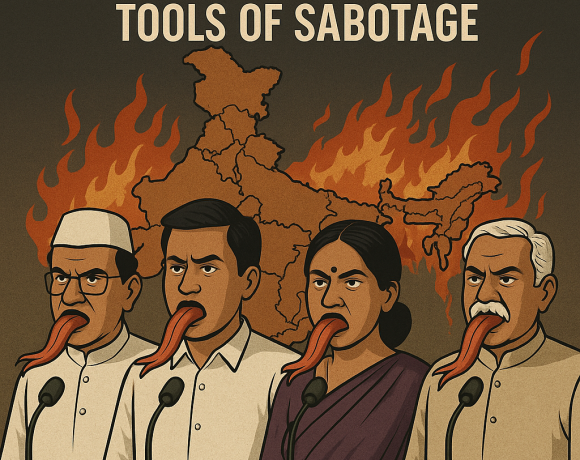

The Babus Rule, The Netas Sign

When Subhash Chandra Garg, the then Finance Secretary of India, quietly decided to resign from the Indian Administrative Service, it wasn’t because of a scandal or political fallout. It was because a file moved in the Ministry of Finance—not through honest dialogue, but through quiet coercion. Garg had opposed a policy proposal to give resolution powers over NBFCs to the Reserve Bank of India. He believed it was ill-conceived and potentially dangerous. The proposal had been pushed by Rajiv Kumar, Secretary of the Department of Financial Services, and backed by none other than Nripendra Misra, the powerful Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister. Garg recorded his dissent formally, following due procedure.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman was not pleased. But not because she disagreed with the logic—by Garg’s own admission, she didn’t even seem to understand the distinction between regulatory and resolution powers. Her objection? That the file contained differing views. She wanted it clean. No dissent. No drama. Just something she could sign without having to explain.

What followed was worse than erasure—it was theatre. Her office refused to accept the file until all the previous note sheets were removed, destroyed, and rewritten as if Garg’s dissent had never existed. It was not a debate. It was a bureaucratic cleansing ritual. Garg allowed it, just this once, to ensure the budget went through. And in that moment, he decided to walk away—for good.

But what does this say about how policies are really made in India?

This was not a minister versus bureaucrat showdown. It was a case of one bureaucrat winning over another. Rajiv Kumar drafted the proposal. Misra backed it. Garg opposed it. Sitharaman simply signed the winner’s side. The real policymaking took place between IAS officers. The minister was the stamp. Not the architect.

This isn’t new. In fact, this is how Indian governance has functioned for decades. Ministers, especially those without deep subject expertise, rely heavily on bureaucrats to conceive, vet, and push through policies. But more often than not, they don’t just rely—they surrender. Once a minister identifies a bureaucrat who “gets things done,” that officer becomes the proxy powerhouse. They liaise with other ministries, draft bills, oversee interdepartmental negotiations, and shape reforms—sometimes with minimal ministerial input.

So what, then, do ministers actually do? Apart from delivering press conferences and riding the highs and lows of public outrage, what is their real function in the machine? When policies fail—as they often do—who gets thrown under the bus? The minister. When they succeed? The credit is split. But the ones who really ran the show continue quietly in the background, shuffled between departments, untouched by public scrutiny.

This bureaucratic supremacy is most entrenched in the Ministries of Finance, Home, Defence, and the Prime Minister’s Office. These are zones of deep statecraft, where files move faster than political understanding. Here, Secretaries are not just administrators; they are co-sovereigns. Sometimes more sovereign than the ministers themselves.

The problem isn’t just bureaucratic overreach. It’s the complete absence of accountability. No one voted for Rajiv Kumar. No one will ever summon Nripendra Misra to a public debate. Their decisions have reshaped India’s economy and security frameworks—and yet, there is no oversight body watching their moves. Meanwhile, Parliament remains a stage, not a forum.

As we circle back to the incident that made Garg resign, the tragedy becomes clearer. A Finance Minister of the world’s largest democracy, and an educated one at that, had to be told what she could sign and only once dissent had been deleted. In any functioning democracy, this would spark outrage. Here, it passed with a whisper.

So we must ask: Who really governs India? If the bureaucrats write the policy, push it, defend it, and erase dissent on their own terms, what is the minister but a well-dressed postman? Worse, who governs the bureaucrats? The answer, disturbingly, is no one.

Until we answer that, we remain a democracy only on paper. Because the babus rule. And the netas sign.