Tariffs, Profits, and Policy Failure: How the U.S. Chose to Hurt Consumers Instead of Harnessing Corporate Wealth

In the aftermath of the U.S.–China trade war, public discourse has focused on tariffs, deficits, and decoupling. But beneath the headlines lies a more revealing truth: the very companies that pushed American manufacturing offshore have profited enormously—untouched by tariffs, shielded from taxation, and unbothered by the inflation they helped trigger. This white paper explores whether the U.S. could have charted a smarter course—by taxing profits instead of products, and by redirecting corporate wealth into national development instead of consumer pain.

Section I: Introduction

In 2018, the United States initiated a sweeping tariff campaign against Chinese imports, under the premise of correcting trade imbalances and protecting American manufacturing. The tariff escalation, which peaked with duties as high as 145% on certain goods by 2025, was framed as a bold geopolitical and economic maneuver. However, this policy shift sparked wide-ranging consequences: consumer price inflation, disrupted supply chains, increased household debt, and retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports.

At the heart of the issue lies a fundamental contradiction: while the U.S. targeted Chinese goods, the major beneficiaries of low-cost Chinese manufacturing were American companies themselves. Brands such as Apple, Nike, Mattel, and Dell routinely import billions of dollars’ worth of finished goods from China—goods they designed, branded, and sold at markups of 3x to 10x. These companies retained substantial profits while passing tariff-related costs down the supply chain to American consumers.

This white paper investigates a critical question:

Could the U.S. have avoided harming its own economy by taxing corporate profits on Chinese imports instead of imposing tariffs?

And further:

What if companies were given the choice to reinvest those profits into U.S. development instead of paying tax—could that have created more jobs, driven growth, and preserved economic stability?

Through a systematic examination of labor markets, supply chains, import volumes, pricing structures, and fiscal outcomes, this review argues that the U.S. government missed a golden opportunity to realign economic incentives. Instead of performative nationalism through tariffs, a targeted policy of profit taxation—or better, conditional reinvestment—could have reshaped American industrial resilience without consumer sacrifice.

Section II: What Products Are Manufactured in China and Exported to the U.S. by U.S. Companies

The U.S.–China trade imbalance is often framed in geopolitical terms, but at its core, it is deeply corporate. A significant proportion of U.S. imports from China are not low-cost, third-party brands, but goods that are manufactured in Chinese factories for U.S.-based multinational corporations—brands that retain the intellectual property, marketing control, and retail margins.

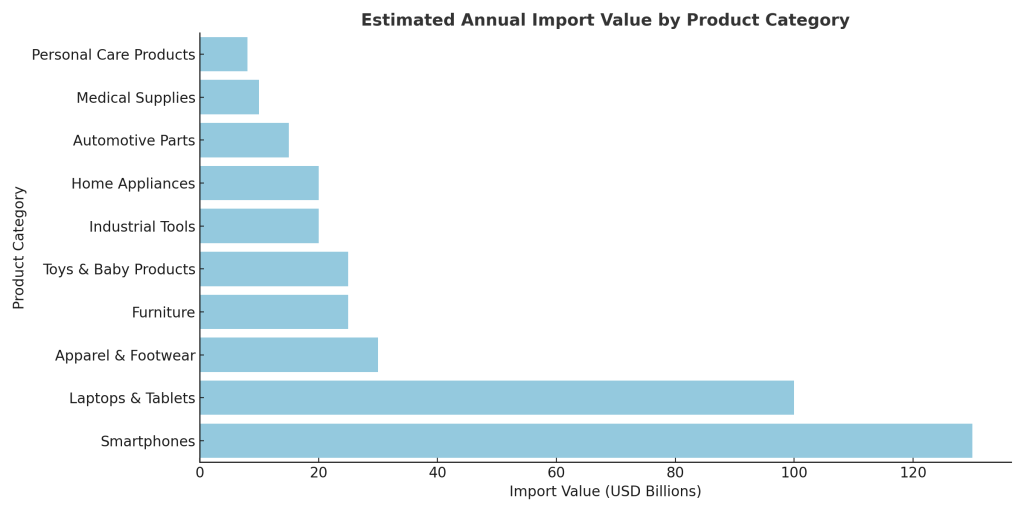

Based on trade data and corporate disclosures, an estimated $400+ billion in goods imported from China annually are directly tied to American corporate supply chains. These span across a wide spectrum of consumer and industrial categories:

-

Electronics: Smartphones, laptops, tablets, and wearable tech comprise the largest slice, with companies like Apple, Dell, HP, and Microsoft assembling nearly all of their flagship devices in China.

-

Apparel and Footwear: Nearly all garments sold by Nike, GAP, Levi’s, and other major fashion brands are produced in Chinese or Southeast Asian factories, with China remaining a key hub.

-

Toys and Baby Products: Iconic products like Barbie dolls and Nerf guns are manufactured under contracts in China by U.S. giants Mattel and Hasbro.

-

Home Goods and Appliances: American kitchen brands such as KitchenAid, Hamilton Beach, and Black & Decker rely on Chinese production for blenders, toasters, and other small appliances.

-

Automotive Components: While final assembly often occurs in the U.S., critical parts—from sensors to wiring harnesses—are imported from Chinese plants.

-

Medical and Personal Care Supplies: PPE, thermometers, grooming tools, and sanitary products used across the U.S. healthcare and consumer sectors are largely Chinese-manufactured, even under American brand labels.

These import patterns are not anomalies—they are the architecture of modern American capitalism. U.S. companies have outsourced production to minimize costs and maximize profits, using China as the world’s manufacturing hub.

The accompanying chart visualizes the estimated annual import volumes by category, reflecting how integral China has become to the American consumer economy.

Section III: Production Cost vs. Retail Price: Who Profits?

At the heart of offshoring is a simple corporate equation: minimize production costs, maximize markup. U.S. companies that manufacture goods in China benefit not only from lower labor and compliance costs but also from the ability to sell these goods domestically at dramatically inflated prices.

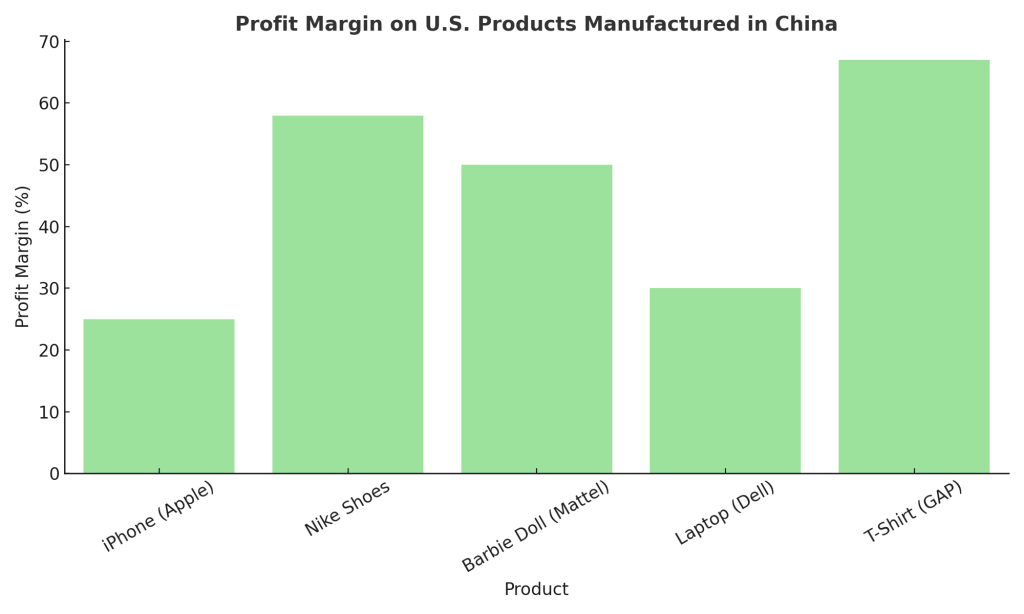

To illustrate, we analyzed five common U.S. consumer products made in China:

-

Apple’s iPhone costs approximately $500 to produce at the factory (FOB). After shipping, logistics, and marketing, Apple spends around $750 per unit—yet sells it at $999, yielding a profit margin of ~25%.

-

Nike sneakers, with a FOB of just $20, incur roughly $30 in additional costs but retail for $120. That’s a 58% margin, driven by branding and market dominance.

-

Mattel’s Barbie doll costs only $5 to produce, with total expenses around $15, but sells for $30, resulting in a 50% margin.

-

A basic GAP T-shirt costing $3 to produce may sell for $30 in stores—a staggering 67%–80%+ profit margin, depending on final pricing and outlet.

These profit margins are not exceptions—they are business models. While a fraction of the retail price covers logistics and advertising, a significant portion is pure retained profit, concentrated in corporate hands.

The accompanying chart reveals the stark disparity between production cost and final consumer pricing, highlighting the inflated margin structure that offshoring enables.

This raises a critical policy question: If companies are profiting this heavily off offshore labor, why weren’t they taxed accordingly—especially during the trade war?

Section IV: Does the U.S. Consume Everything It Imports?

One common misconception in public discourse is that the United States imports more than it needs, leading to unnecessary trade deficits. In reality, however, most of what the U.S. imports from China is aligned with actual domestic consumption. There is minimal evidence of surplus or stockpiling—only systemic dependency.

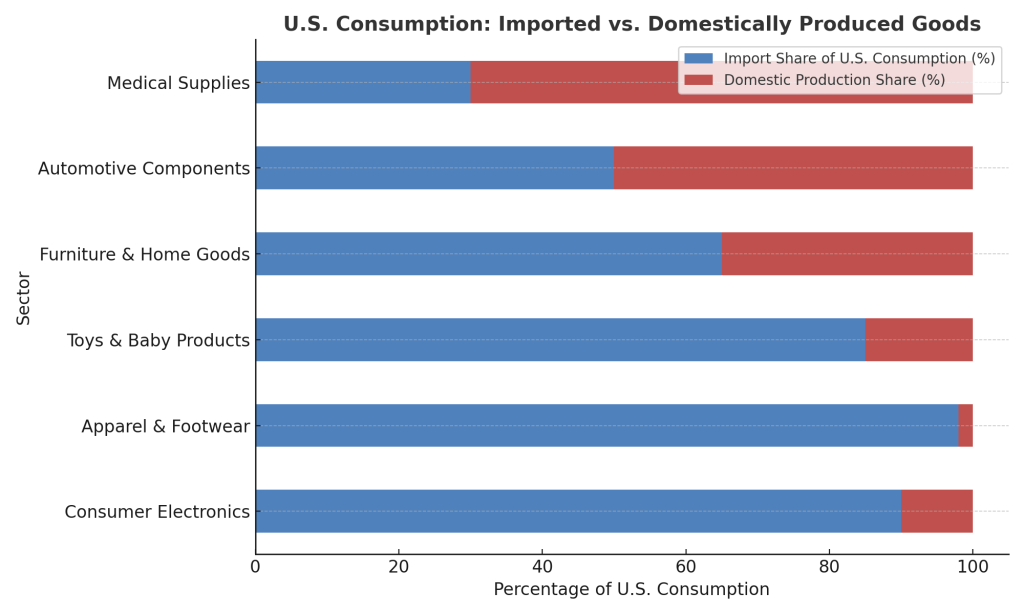

Based on sector-wise analysis, here’s the breakdown of import vs. domestic production share:

-

Consumer electronics: ~90% of U.S. consumption is met through imports, particularly from China. Domestically manufactured electronics are rare and limited to high-end or defense-oriented niches.

-

Apparel and footwear: The U.S. now produces only about 2% of the clothes and shoes it consumes. Over 98% is imported, with China playing a leading role despite diversification into Southeast Asia.

-

Toys and baby products: With an import share of 85%, the American toy industry is almost entirely offshore—domestic production exists only for specialized or artisanal lines.

-

Furniture and home goods: Around 65% of these products are imported, while the remaining 35% is produced in domestic hubs like North Carolina and Michigan.

-

Automotive parts: This is more balanced, with roughly 50% of components sourced abroad—mostly from China, Mexico, and Canada—while the rest are domestically made.

-

Medical supplies: Only about 30% of consumption is met through imports, as the U.S. retains some domestic capacity for pharmaceuticals and essential medical devices.

The chart illustrates that for most goods—particularly consumer-facing products—imports are not just supplemental, they are foundational. Domestic manufacturing simply does not exist at the required scale to replace current import levels.

Conclusion: The U.S. does not over-import from China—it imports because it has systematically outsourced production to meet its own consumption needs. There is no meaningful surplus, only dependence.

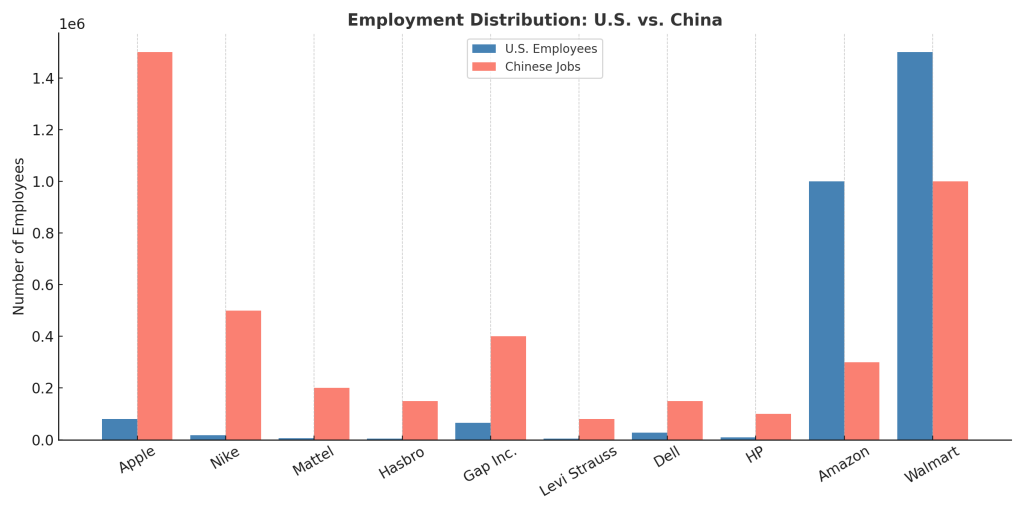

Section V: Chinese vs. U.S. Employment Footprint in the Same Supply Chain

While American companies often tout their domestic employment figures to project patriotism, the labor reality of their business models tells a different story. For every retail, corporate, or marketing job in the U.S., these companies rely on 5 to 30 times more workers in China to actually manufacture their products.

Here’s how the labor distribution looks for key companies:

-

Apple employs around 80,000 Americans, mostly in retail and tech roles—but an estimated 1.5 million Chinese workers are employed through Foxconn and Pegatron to assemble Apple devices.

-

Nike, with only 17,000 U.S. employees, relies on approximately 500,000 workers in Chinese and Southeast Asian factories for production.

-

Mattel and Hasbro, the toy giants, maintain modest U.S. headcounts but depend on hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers to make the very toys that fill American shelves.

-

Gap and Levi Strauss, leading American apparel brands, employ more people in China’s garment sector than in their U.S. corporate and retail operations.

-

Amazon and Walmart dominate U.S. employment with millions of domestic jobs, but still rely heavily on Chinese manufacturing labor—with Walmart indirectly tied to over a million Chinese factory jobs through suppliers.

The bar chart provides a visual comparison, underscoring the staggering disparity between the offshore production workforce and the onshore employment narrative.

Conclusion: American brands are not just customers of Chinese manufacturing—they are structurally dependent on Chinese labor for their very existence. While profits remain in the U.S., the bulk of hands that produce these goods are overseas.

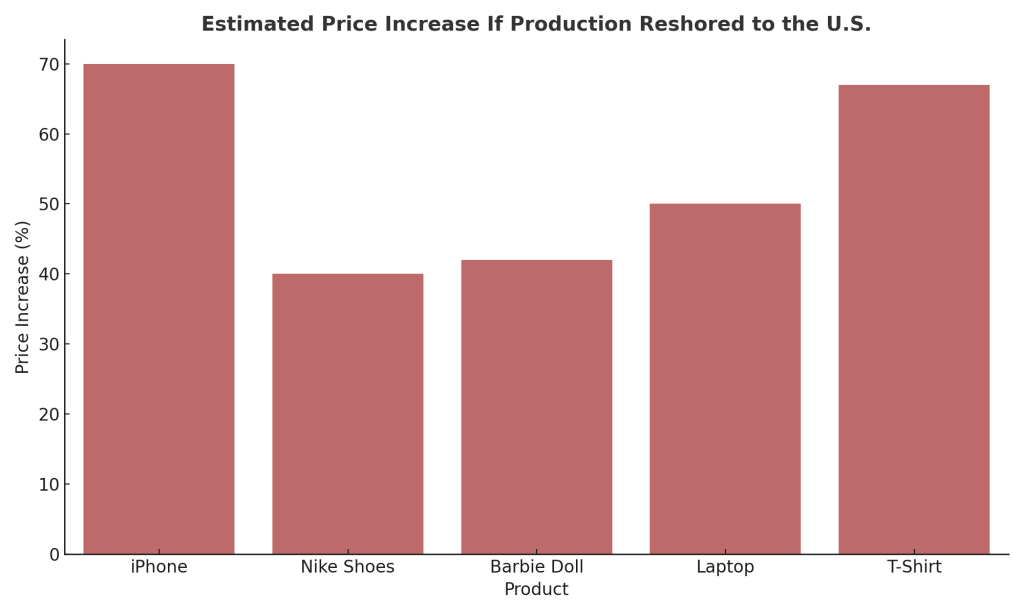

Section VI: What if Production Was Shifted to the U.S.?

Calls to “bring manufacturing back to America” are politically popular, but economically perilous unless they’re backed by automation, subsidies, or radical supply chain redesign. The U.S. simply cannot replicate Chinese cost structures, especially in labor-intensive sectors.

We examined five common consumer goods and projected their price impacts if full production was shifted from China to the U.S., with no change in corporate markup expectations:

-

Apple’s iPhone, currently priced at $999, would jump to ~$1,699. The rise is driven by U.S. labor costs, which are 5–6x higher than Chinese assembly wages.

-

Nike shoes, retailing for $120, would see a ~40% increase to $168.

-

Barbie dolls, simple yet labor-heavy, would climb from $30 to $42.50, a 42% increase.

-

Laptops, where labor is a smaller portion of total cost, would still rise from $1,200 to $1,800—a 50% jump due to domestic assembly, testing, and compliance costs.

-

GAP T-shirts, currently $30, would surge to ~$50 if sewn, packaged, and shipped within the U.S.

The accompanying chart highlights the price escalation across categories—underscoring the consumer-level economic shock that a sudden reshoring strategy would trigger.

Conclusion: Reshoring under current labor economics and corporate profit expectations would not just be expensive—it would be inflationary on a national scale. Unless production is automated or heavily subsidized, American consumers would bear the brunt of “Made in America.”

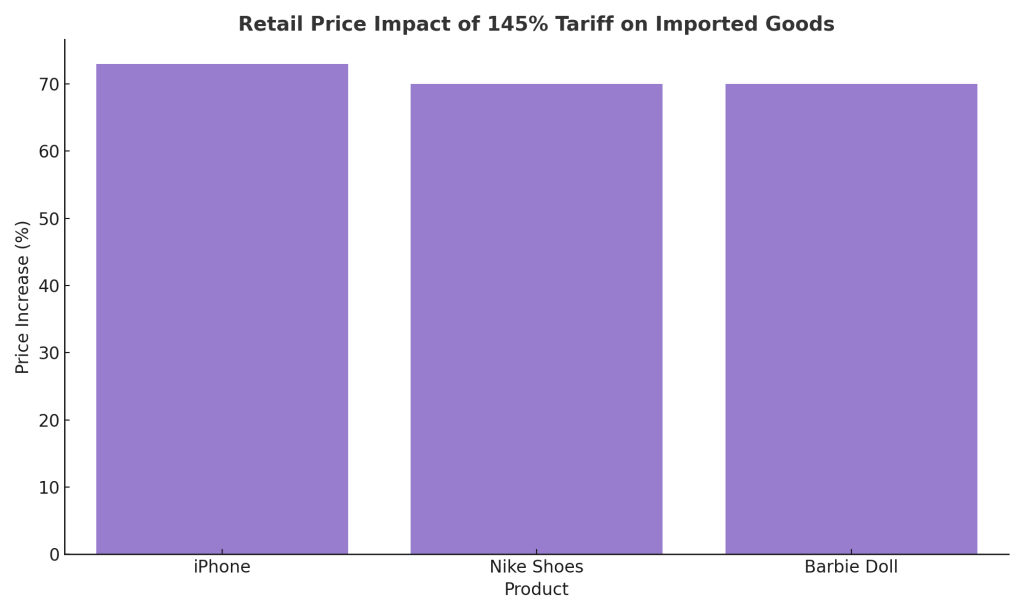

Section VII: The Trump Tariffs and Their Economic Fallout

Between 2018 and 2020, the Trump administration escalated a trade war against China, ultimately applying tariffs of up to 145% on a wide range of imported goods. While marketed as a strategic move to reduce U.S. trade deficits and bring jobs back home, the policy led to severe domestic repercussions, particularly in terms of inflation and consumer costs.

We analyzed the price impact of a 145% tariff on several popular consumer products:

-

The iPhone, already expensive at $999, would surge to $1,725, a 73% increase, if the full tariff were passed to consumers.

-

Nike shoes, rising from $120 to $204, see a 70% hike, despite being mass-market staples.

-

A Barbie doll, normally priced at $30, would inflate to $51, again a 70% increase, purely due to the tariff burden.

While these tariffs generated approximately $55 billion/year in government revenue at their peak, the cost was indirectly paid by American consumers—not China. Simultaneously, retaliatory tariffs from China hit American exporters in agriculture, automotive, and tech sectors, damaging U.S. competitiveness abroad.

Economic fallout included:

-

Higher inflation, especially in durable goods and electronics

-

Reduced consumer purchasing power

-

Increased credit card usage and household borrowing

-

Slowed business investment due to cost uncertainty

-

Job losses in export-sensitive U.S. industries

In short, the tariffs became a self-inflicted economic wound. The government gained revenue, but at the cost of undermining its own economic engine—consumer demand.

Conclusion: The Trump tariffs were politically dramatic but economically shortsighted. They hurt American wallets more than Chinese boardrooms. Worse, the U.S. could have achieved much of the same fiscal benefit by taxing corporate profits from China-linked imports—without torching its internal economy.

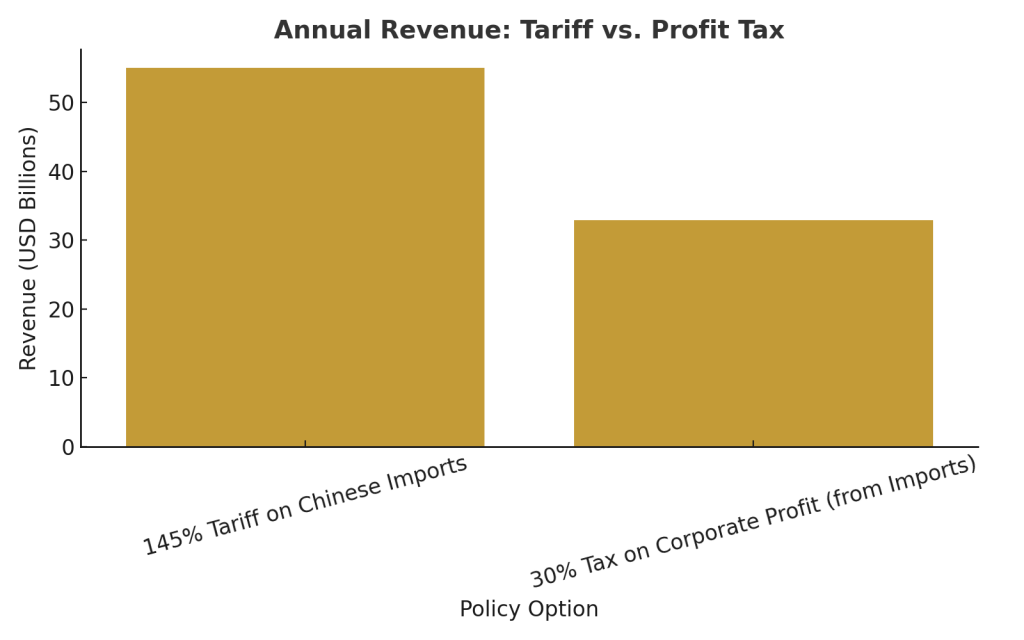

Section VIII: Why a 30% Profit Tax Would Have Been Better

While the Trump-era tariffs generated significant revenue—around $55 billion per year—they came with substantial collateral damage: inflation, reduced consumption, trade retaliation, and declining consumer confidence. But what if the U.S. had chosen a different path?

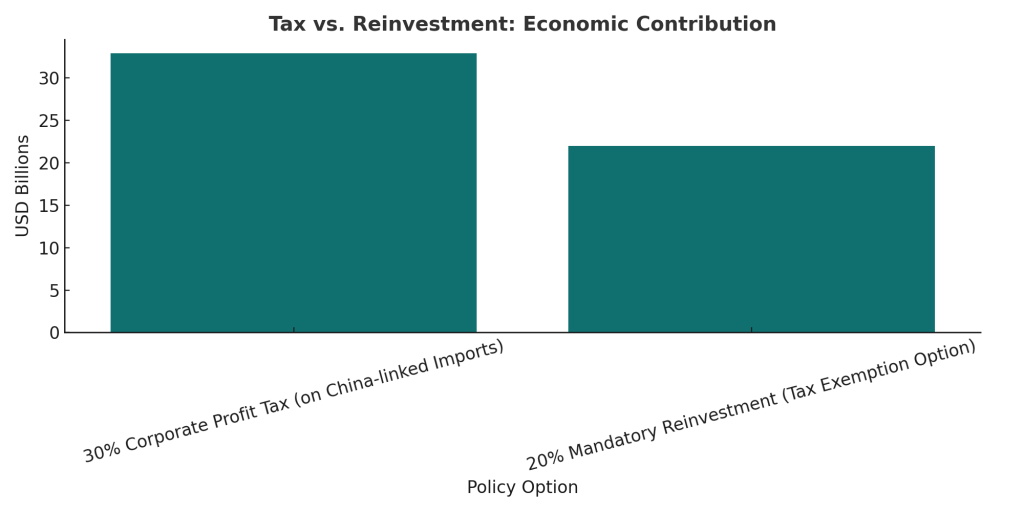

Instead of taxing imported goods at the point of entry, the government could have implemented a 30% corporate tax on profits derived from Chinese imports. Based on profit estimates from major U.S. brands (e.g., Apple, Nike, Mattel), this could have generated ~$32.9 billion per year in federal revenue.

Why this would have been superior:

-

Consumer-friendly: Prices would remain stable. The cost burden wouldn’t be passed to households.

-

Targeted accountability: Only companies profiting from offshoring would pay—not every consumer.

-

Revenue stability: Profits are more predictable than volatile global trade flows.

-

No trade war risk: China would have had no legal or diplomatic basis for retaliation.

Political Impact

This alternative would have achieved fiscal goals without:

-

Damaging the domestic economy

-

Triggering global supply chain instability

-

Harming small businesses and exporters

Economic Logic

In pure economic terms, a profit tax would have produced nearly two-thirds of the tariff revenue while preserving purchasing power. The accompanying chart visualizes the trade-off, highlighting how a more elegant, less damaging policy was available—but ignored.

Conclusion: The U.S. could have raised nearly as much money, held corporations accountable, and avoided harming its own people—all by taxing profit, not products. That it didn’t reflects a failure of both political will and economic imagination.

Section IX: Proposed Solution: Conditional Reinvestment Instead of Taxation

Rather than imposing a blanket tax or a damaging tariff, the U.S. government could have introduced a more strategic and growth-oriented policy:

Give companies a choice—either pay a 30% tax on profits from China-linked imports, or reinvest 20% of those profits into U.S.-based economic development.

This model balances accountability with opportunity.

Estimated Impact:

-

A 30% profit tax could yield $32.9 billion/year in government revenue.

-

Alternatively, a 20% mandatory reinvestment would redirect $22 billion/year directly into the U.S. economy—fueling industrial rejuvenation and job creation.

Where Would the Money Go?

-

R&D and innovation centers

-

Reshoring-capable industrial parks

-

Skilled labor training and vocational education

-

Infrastructure and logistics modernization

-

Clean energy and automation tech

-

University-industry research hubs

Economic Benefits:

-

Stimulates white-collar and blue-collar job growth

-

Strengthens domestic supply chain resilience

-

Repositions America for long-term competitiveness

-

Offers a growth multiplier effect, with $22B potentially catalyzing $50–60B in GDP gains over time

Corporate Incentive:

Rather than resist taxation, corporations would have the option to:

-

Retain profits and reinvest domestically

-

Build goodwill and brand reputation

-

Influence local development (e.g., infrastructure near HQs or factories)

Conclusion: This policy isn’t just tax reform—it’s economic regeneration by design. It channels profit-driven offshoring into purposeful national development. It avoids the harm of tariffs while incentivizing a return to industrial relevance.

Section X: Conclusion

Yes, the U.S. government could have avoided much of the economic self-harm inflicted during the 2018–2020 trade war by simply taxing corporate profits on Chinese imports instead of imposing aggressive tariffs. It could have protected consumers, maintained demand, controlled inflation, still generated revenue, and avoided unnecessary retaliation. Instead, it chose performative protectionism over strategic development.

Even better, the government could have offered companies an alternative: invest 20% of those profits in U.S. business development instead of paying the tax. That would have supercharged domestic growth, fueled white-collar employment, and still ensured revenue neutrality. What the country got instead was inflated prices, weaker consumption, and policy theater.

This white paper has demonstrated that:

-

U.S. companies profit immensely from Chinese labor while employing a fraction of those numbers domestically.

-

These profits are protected, not taxed—even when consumer costs surge due to tariffs.

-

A corporate profit tax, or conditional reinvestment mandate, could have achieved the same fiscal objectives with far greater economic and social benefits.

This wasn’t just a missed opportunity. It was a deliberate policy failure that prioritized optics over outcomes. And unless this imbalance is addressed, the American economy will continue to export labor, import inflation, and defend corporate excess at the expense of its own people.

This white paper has been prepared in collaboration with our research partners at Statscope Research. All data visualizations, comparative models, and policy analyses were developed using publicly available economic indicators, corporate disclosures, and trade statistics, supported by independent projections.

For research inquiries please contact:

📩 statscope@bharatpulsenews.com