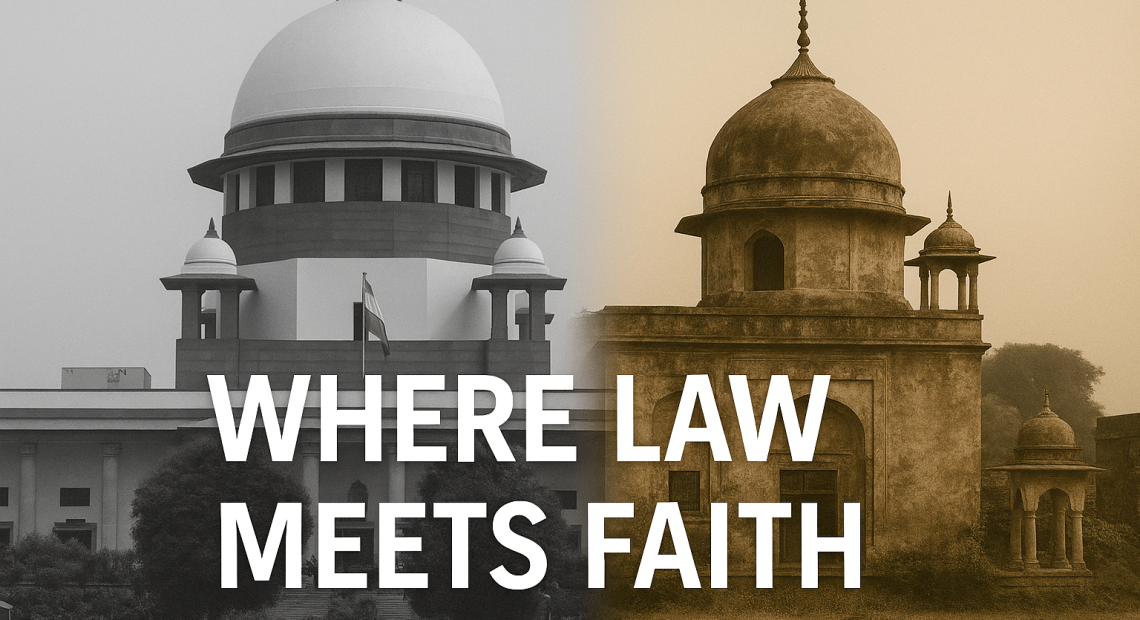

Supreme Court’s Convenient Secularism: Preamble in Banu Mushtaq, Amnesia in WAQF Board

The Supreme Court seems to have developed a very curious relationship with the Preamble of the Constitution. At times, it is treated as holy scripture, waved triumphantly to remind citizens of their secular duty. At other times, it is shoved into a dark corner, conveniently forgotten when its presence would be rather inconvenient. The difference between these two approaches can be seen most clearly if one compares the Court’s handling of the Waqf Board amendment case and the Banu Mushtaq–Mysuru Dasara controversy. The timeline is clear: first came the Waqf Board hearings, where the Preamble was nowhere to be seen. Later came the Banu Mushtaq case, where the very same Preamble was dramatically pulled out and put on centre stage like a long-lost relic.

During the Waqf Board hearings on the 2025 Amendment, the Court bent over backwards to express concern about non-Muslims being included in the governance of Waqf institutions. Suddenly, the rhetoric was all about essential religious practices, denominational rights, and the fragile sanctity of Islamic trusts. Where was the Preamble then? Where was the noble secular spirit that insists the State must not discriminate between religions? The Court did not summon the Constitution’s opening lines to defend equality. Instead, it stayed provisions of the law and practically treated secularism as an unwanted guest in its own courtroom. Apparently, the Preamble had applied for leave that day.

Fast forward to Mysuru, where a petition was filed against author Banu Mushtaq inaugurating the state’s grand Dasara festivities. And lo and behold, the Preamble reappeared! This time, the judges were positively glowing with constitutional pride. “We are a secular country,” they reminded us with an air of discovery, as though they had just unearthed the words from some forgotten manuscript. Secularism, which had been conspicuously absent during the Waqf case, was now suddenly the guiding star. A Muslim inaugurating a Hindu festival? Perfectly constitutional, they said. The Preamble had been dusted off, polished, and paraded as if it were the chief guest of the festival itself.

So what does this selective invocation tell us? That the Supreme Court practices a buffet-style secularism. Take some Preamble when serving a sermon on inclusivity, but leave it aside when a minority trust demands exclusivity. When the case involves the majority community being reminded of their duty to embrace diversity, the Preamble becomes mandatory reading. But when it comes to minority institutions being asked to open their doors, suddenly the same secular spirit is treated like an optional elective. It is as if the Court runs a lending library for constitutional values: available on request, return date flexible, use subject to mood.

This double standard is not just amusing; it is corrosive. It makes the judiciary appear less like an impartial guardian of constitutional principles and more like a part-time orator tailoring speeches to suit the occasion. It tells citizens that secularism is not a permanent compass but a decorative slogan. Worse, it signals that the judiciary is willing to ration out constitutional values depending on who is at the receiving end. One day it is Banu Mushtaq being defended with lofty invocations; another day it is the Waqf Board being shielded from the very same ideals.

And here lies the ultimate irony: the Court has managed to make the Preamble itself appear partisan. The very document meant to embody India’s highest principles is being showcased like a festival prop in one case and hidden like an embarrassing relative in another. Perhaps the judges should clarify whether the Preamble is meant to guide the Republic every day, or only on days when Mysuru celebrates Dasara. Because right now, the message is clear: the Preamble is less of a constitutional foundation and more of a stage curtain—drawn and dropped depending on the script of the day.