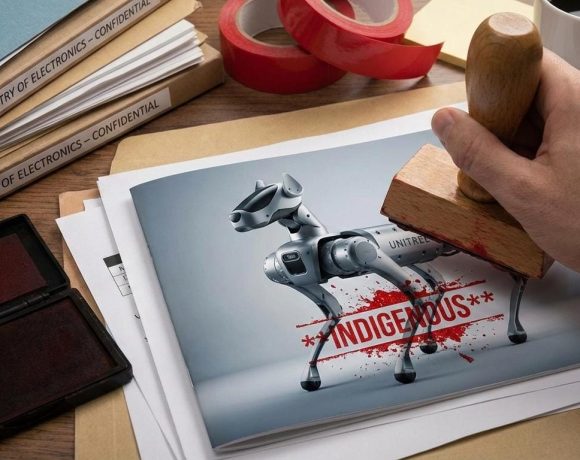

Project Cheetah: A Bold Vision Undermined by Poor Planning and Avoidable Mistakes

It was supposed to be a roaring success—India’s grand plan to reintroduce the cheetah, the fastest land animal, to its historical home. Project Cheetah was painted as a global conservation masterstroke, complete with dramatic airlifts from Africa and ceremonial photo-ops in Kuno National Park. Seventy years after India saw its last cheetah, the government triumphantly announced its return with all the fanfare of a space launch. Unfortunately, the project has since unfolded more like a tragic sitcom: starring confused cats, a shrinking habitat, and a cast of bureaucrats who clearly skipped their homework.

Fast forward to today, and the situation on the ground is anything but majestic. Nine adult cheetahs are dead. Three cubs didn’t make it. The survivors are pacing nervously in a park barely big enough for their needs. And just recently, one of the few remaining females—Jwala—along with her cubs, was nearly stoned by angry villagers after killing a calf. In case anyone forgot, predators tend to hunt. But don’t worry—the state’s response has been robust: more guards, some press releases, and lots of finger-pointing. Truly inspirational.

Despite the promise of Project Cheetah, its story so far reads like a checklist of avoidable errors, all executed with unshakeable confidence. The cheetahs themselves seem to be doing their best. It’s the humans—specifically, the ones running the show—who appear to be in dire need of relocation, preferably to a management refresher course.

Let’s begin with the masterstroke of planning: releasing all the cheetahs into a single park, Kuno, which conveniently happens to have the carrying capacity of a medium-sized cat cafe. Experts pointed out early on that Kuno could host no more than 20 cheetahs. So, naturally, the plan was to bring in 20. And then breed them. Because clearly, cheetahs understand administrative ceilings and will politely stop reproducing when the park reaches code capacity.

Then there’s the villagers—yes, the same people who were never properly briefed on what it means to live near free-ranging African predators. The recent attempt by locals to attack Jwala and her cubs after the calf-killing incident wasn’t an isolated outburst. It was a predictable outcome of neglecting human-wildlife dynamics. The forest department’s brilliant response? Send a team to “calm things down” and assure people that cheetahs don’t pose a threat—as long as, of course, your livestock doesn’t wander too far. Or you don’t mind the occasional “wildlife encounter.”

Health monitoring was another dazzling display of oversight. Several cheetahs died from complications exacerbated by radio collars, which caused skin infections and sepsis. Wildlife experts warned that India’s humid, monsoon climate isn’t ideal for these collars. But when has scientific caution ever stood in the way of a good press release? We soldiered on, right into a pile of carcasses, and then decided to “review the collar design.” Progress.

And let’s not forget the urgency of it all. Project Cheetah was launched with the kind of speed one usually reserves for disaster response or election-year schemes. The animals were brought in, released, monitored (loosely), and expected to settle in, thrive, and multiply—all in record time. The fact that several died soon after release? A minor footnote in the larger narrative of “getting things done fast.”

Of course, the real champions of this story are the experts who weren’t listened to. Conservation biologists across India and abroad raised red flags about ecological suitability, prey base limitations, and the risks of isolated reintroduction. But who needs boring old peer-reviewed science when you have bold ambition and high-definition camera crews?

To add a final touch of brilliance, no real effort was made to establish wildlife corridors or alternate habitats. So when the cheetahs want to expand their territory—as wild animals tend to do—they’re met with fences, villages, and more angry locals. It’s almost like we wanted them to fail, just so we could blame the cheetahs for not adjusting to “Indian values.”

Could things have been done differently? Oh, absolutely. We could have built multiple habitats before importing animals. We could have actually worked with communities instead of assuming they’d be thrilled to lose livestock for the national cause. We could have heeded ecological studies, monitored animal health with better tech, and moved slowly and adaptively—like every successful wildlife reintroduction program in the world.

But then, where’s the glory in that? Where’s the photo opportunity?

Still, all is not lost. We’re told this is a “learning phase.” And nothing screams “learning” like endangered animals dying and villagers nearly rioting. What comes next is a promised course correction. More scientific involvement, better training, community outreach—maybe even functional collars. So there’s hope. Real, tangible, totally believable hope.

After all, if there’s one thing the Indian government has consistently shown, it’s the ability to admit mistakes, embrace expert opinion, and act transparently with ecological sensitivity. Surely, this time will be different. Right?