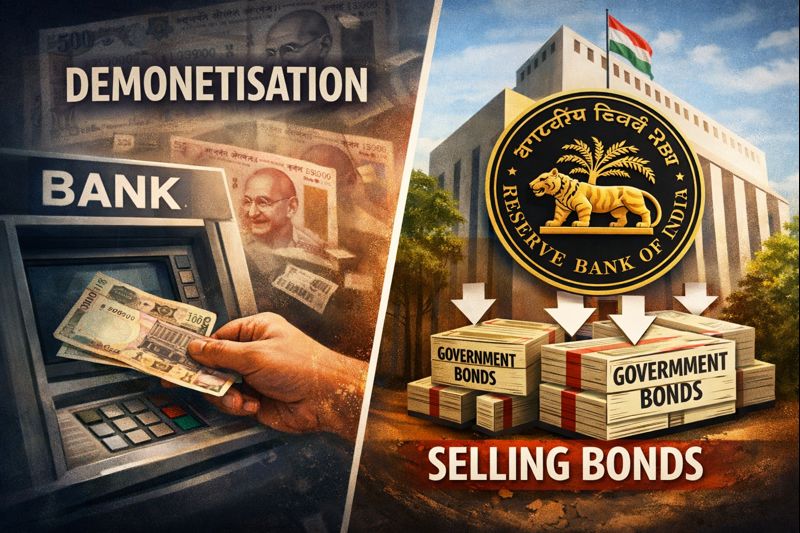

From Cash Shock to Liquidity Surplus: Why RBI Became a Net Seller After Demonetisation

Introduction

In simple terms, this article explains what really happened to money in the system after demonetisation and why the Reserve Bank of India later had to remove money instead of adding it. A common belief is that demonetisation created such a severe cash shortage that RBI was forced to print money to keep banks afloat. The RBI’s own bond purchase and sale data tells a very different story.

At its core, this article answers a basic question. If demonetisation was meant to pull cash out of the system, why did RBI end up selling government bonds to absorb excess liquidity instead of buying bonds to inject money? The answer lies in how demonetisation altered the location of money rather than its existence.

Understanding RBI’s OMO Framework

Open Market Operations, or OMOs, are the RBI’s primary tool to manage durable liquidity in the banking system. When RBI buys government bonds, it injects money into banks. When it sells government bonds, it absorbs money from banks. The direction of OMO activity therefore reveals whether RBI believes the system has too little money or too much.

OMO activity is not about funding government spending. It is about ensuring that interest rates, credit availability, and financial stability remain aligned with economic conditions. This distinction is critical when analysing the demonetisation period.

Liquidity Conditions Before Demonetisation

In the financial year before demonetisation, RBI was a large net buyer of government securities through OMOs. This reflected relatively tight liquidity conditions in the banking system. Credit demand existed, government cash balances fluctuated, and RBI needed to inject money to keep overnight rates and funding markets stable.

In simple terms, before demonetisation, RBI was already supporting liquidity using conventional monetary tools. There was no extraordinary stress that required radical intervention.

The Demonetisation Shock and Forced Deposit Surge

Demonetisation in November 2016 abruptly invalidated high-value currency notes. This did not destroy money permanently. Instead, it forced households, traders, and businesses to deposit cash into banks in order to exchange or legitimise it.

As a result, bank deposits surged sharply within weeks. This liquidity did not come from RBI printing new money. It came from existing cash being pushed into the formal banking system. Banks suddenly found themselves flush with funds even as credit demand slowed due to economic disruption.

Why RBI Cut Back Bond Purchases During Demonetisation

During the demonetisation year, RBI’s net bond purchases collapsed compared to the previous year. This was not a coincidence. The forced inflow of deposits meant banks were already sitting on excess liquidity.

Injecting more money through bond purchases at this stage would have been unnecessary and potentially destabilising. RBI’s restraint during this period shows that demonetisation itself had created surplus liquidity conditions inside banks.

Post-Demonetisation Reality: RBI Turns Net Seller

In the financial year following demonetisation, RBI became a net seller of government bonds through OMOs. This is the most important data point in the entire debate.

Bond sales are used only when there is excess liquidity in the system. RBI was not supporting banks. It was cleaning up surplus cash created by demonetisation-driven deposits that were not being absorbed by lending or investment.

This shift decisively disproves the claim that RBI printed money to offset demonetisation. If demonetisation had caused a persistent liquidity shortage, RBI would have been forced to buy bonds aggressively. Instead, it did the opposite.

What the OMO Data Proves About Demonetisation

The sequence of events is clear. Demonetisation forced cash into banks. Deposits surged. Credit demand weakened. Liquidity became excessive. RBI responded by absorbing money, not creating it.

This supports the view that demonetisation was a cash-centralisation shock rather than a monetary expansion. It temporarily shifted money from households to banks, giving the formal system more control over liquidity, even though this control was not permanent.

Why Cash Still Returned Despite Liquidity Absorption

Despite RBI absorbing liquidity through bond sales, cash in circulation gradually returned and eventually exceeded pre-demonetisation levels. This happened because RBI reissued new notes, economic activity recovered, and public preference for holding cash did not disappear.

OMO operations manage bank liquidity, not individual cash preferences. Once deposits became freely withdrawable, money flowed back into physical form. Demonetisation altered the system’s balance sheet temporarily, not long-term behaviour.

Conclusion

Demonetisation did not lead RBI to print money to rescue the financial system. The central bank’s own OMO data shows that the opposite happened. Demonetisation created excess liquidity inside banks, forcing RBI to sell bonds and absorb money to maintain stability.

As a policy tool, demonetisation failed to reduce cash usage permanently. However, it succeeded in temporarily centralising liquidity and resetting the deposit base of the banking system. RBI’s role after demonetisation was not that of an architect of monetary expansion, but of a janitor cleaning up a surplus created by an administrative shock.

The OMO numbers strip away political narratives and reveal a simpler truth. Demonetisation moved money around. RBI then had to stabilise the consequences.