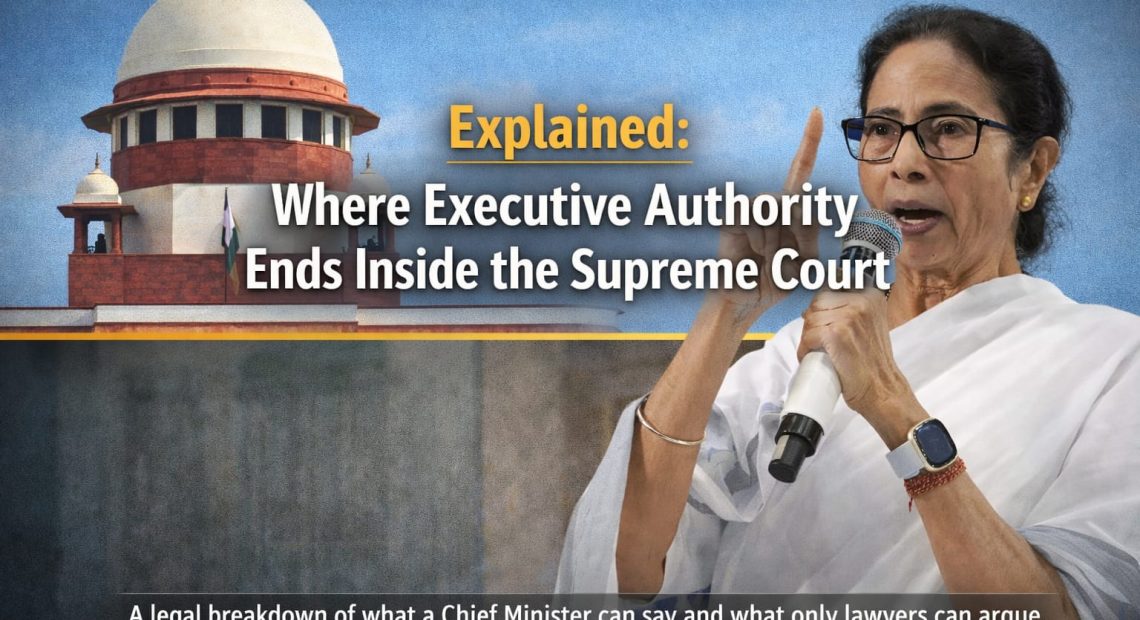

Explained: Why the Supreme Court Let Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee Speak, Then Asked Her Lawyers to Take Over

The recent Supreme Court hearing in which Mamata Banerjee personally addressed the bench triggered predictable confusion. Social media immediately split into two camps: one claiming she had no right to speak because she is not an advocate, and the other treating the episode as proof that political power bends judicial procedure. Neither reading is legally accurate. What unfolded was neither illegal nor extraordinary, but it was also not an open invitation for a Chief Minister to argue a case. It was a tightly controlled exercise of judicial discretion.

At the outset, it is important to understand that the Supreme Court is not bound by the same procedural rigidity as subordinate courts. Under Article 145 of the Constitution, the Supreme Court has the power to frame its own rules and regulate its own procedure. This constitutional autonomy allows the bench to decide who may address it, in what capacity, and for what limited purpose. This authority exists independently of the Advocates Act.

The Advocates Act, 1961 does not create an absolute bar on non-advocates speaking in court. Section 32 of the Act explicitly states that a court may permit a person who is not enrolled as an advocate to appear before it in any particular case. This provision is discretionary, not a right, and it is exercised sparingly. When the Supreme Court allows a non-advocate to speak, it does so because it believes the submission will assist the court, not because the speaker is entitled to be heard.

A sitting Chief Minister occupies a distinct constitutional position. As the head of the state executive, she is not merely a litigant but the authority ultimately responsible for the actions, intent, and compliance of the state government. In cases involving state conduct, administrative defiance, or execution of constitutional duties, the court may choose to hear directly from the person who controls the machinery of governance. This is particularly relevant in proceedings under Article 32 or Article 136, where the court is concerned with constitutional compliance rather than routine adjudication.

What the court permits in such situations is not legal argument, but executive clarification. A Chief Minister may place on record the state’s intent, offer assurances, accept or reject responsibility, or clarify factual positions. These statements can carry legal weight because they may amount to binding undertakings by the state. Courts routinely record such assurances and rely on them while framing directions. If breached, they can even give rise to contempt proceedings. That legal consequence alone distinguishes such statements from political speeches.

However, there is a clear and non-negotiable boundary. The moment a submission shifts from explaining executive intent to interpreting statutes, contesting constitutional provisions, or citing precedent, it crosses into advocacy. Advocacy is the exclusive domain of enrolled lawyers. That is why the judges intervened and asked her to let her lawyers argue. This was not a rebuke. It was the court enforcing the separation between executive accountability and legal reasoning.

There are also practical reasons for this intervention. Supreme Court hearings are precedent-driven. Judges expect precise references to case law, statutory language, and constitutional doctrine. Lawyers are trained to answer judicial queries within this framework. Allowing a political executive to continue beyond limited clarification risks diluting the legal record, creating ambiguity, and turning a judicial hearing into a narrative exercise. Courts are acutely conscious of this risk, especially in politically sensitive matters.

Importantly, such permission does not create precedent. The Supreme Court has repeatedly made it clear that discretionary allowances under Section 32 of the Advocates Act or under its inherent powers are case-specific. They do not weaken the Advocates Act, nor do they open the door for politicians or officials to routinely address courts. The default rule remains unchanged: legal arguments are to be made by advocates on record.

The episode therefore reflects judicial control, not judicial indulgence. The court allowed a limited intervention to extract accountability and clarity from the highest executive authority of the state. Once that purpose was served, it firmly restored the primacy of counsel-led argumentation.

In the end, the appearance may well have been political theatre or a show of defiance aimed at a domestic audience. But the outcome told a different story. The Chief Minister spoke, the court listened briefly, and then the court drew a clear line. It was a reminder that however powerful the executive may be outside, inside the courtroom there remains an authority it cannot talk over, bypass, or ignore.