Delhi High Court Sees a Threat, Mumbai High Court Sees a Contract: The Çelebi Contradiction

At the core of this legal tangle is a company that handles what most passengers never think about—baggage loading, aircraft refueling, tarmac coordination, and cabin cleaning. Ground handling may sound mundane, but it forms the logistical backbone of airport operations. More importantly, it grants the contractor access to aircraft interiors, cargo, and runways, making it a highly sensitive function from a national security standpoint.

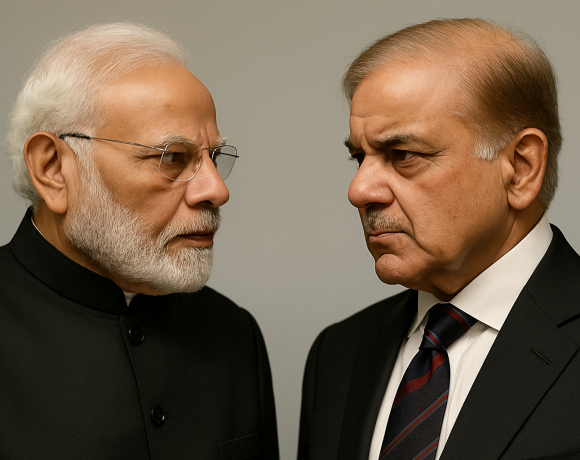

Çelebi Airport Services, a Turkish firm operating in India for years, was entrusted with these services at several airports, including the Mumbai International Airport. However, the geopolitical context shifted after Turkey openly backed Pakistan on multiple global platforms, including at the United Nations. This prompted Indian security agencies to re-evaluate Turkish entities operating in sensitive sectors. The Bureau of Civil Aviation Security (BCAS), after what it claims was a due assessment, revoked Çelebi’s security clearance—a move that would normally disqualify any vendor from operating in secure zones of Indian airports.

In line with this development, Mumbai International Airport Limited (MIAL) moved to terminate Çelebi’s contract and floated fresh tenders to appoint a replacement. Çelebi, unsurprisingly, approached the judiciary to challenge this termination. This is where the story split into two—one narrative playing out in Delhi, where national security took precedence, and another in Mumbai, where contractual obligations overshadowed security warnings.

Delhi High Court’s Response: National Security First?

In Delhi, Çelebi challenged the revocation of its security clearance by the BCAS, claiming the move was arbitrary and lacked procedural fairness. The company argued it was not given a chance to respond, and the decision had been sprung without prior notice, impacting its operations and reputation. On the surface, it appeared to be a case about administrative overreach—until the government stepped in with a far more serious assertion.

Representing the Centre, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta told the Delhi High Court that the revocation was based on inputs received from intelligence agencies and involved matters of national security. Given the sensitivity of the evidence, the government submitted its material in a sealed envelope. This sealed-cover practice, while controversial, is still permissible under Indian jurisprudence in cases involving classified information. The judge, Justice Sachin Datta, accepted the government’s rationale and deferred to the state’s security assessment. He did not demand full public disclosure of the threat posed but agreed that the state had the prerogative to act swiftly in national interest.

This posture signaled a judicial understanding that some domains—especially those intersecting with strategic infrastructure and foreign policy—require courts to step back and allow the executive to act decisively. The case was not dismissed outright, but the deference to national security made it clear that the court would treat such matters with the seriousness they deserve. Importantly, the bench acknowledged that even if procedural rights are vital, they cannot outweigh credible threats to India’s aviation security.

Mumbai High Court’s Response: A Contractual View?

In stark contrast, the Bombay High Court viewed Çelebi’s challenge not through the lens of national security, but as a dispute over contract termination and bidding irregularities. When Çelebi approached the court after MIAL attempted to end its contract and invite fresh bids, the case was framed purely in commercial terms: Was due process followed? Was the termination arbitrary? Were the fresh bids floated in a manner that disadvantaged the incumbent?

Crucially, unlike in Delhi, there was no submission of security-related concerns in a sealed cover. No formal intervention came from the Ministry of Civil Aviation or BCAS to support MIAL’s actions. The entire proceeding unfolded as if this was a routine matter between a private airport operator and a service vendor. The court, relying solely on the documents and arguments presented, granted an interim stay on the bidding process and restrained MIAL from awarding the contract to any new entity until the matter was heard in full after the summer recess.

By doing so, the Bombay High Court effectively maintained Çelebi’s presence at one of India’s most high-traffic airports—even though the same company’s security clearance had been stripped at the national level. The court’s response wasn’t unlawful; it was simply built on a case that had been deliberately stripped of any national security context. Had MIAL or the central agencies invoked even a hint of intelligence concern, the court might have taken a different approach. But with no such plea before it, the court treated the matter like any other dispute over a public tender.

Who Dropped the Ball in Mumbai?

If Delhi’s courtroom drama played out like a state security briefing, Mumbai’s resembled a corporate arbitration hearing. The question then arises: who failed to frame the Çelebi issue for what it truly was in Mumbai? The answer begins with Mumbai International Airport Limited (MIAL). As the entity directly terminating Çelebi’s contract, it was their responsibility to present a robust legal and strategic justification. And yet, MIAL inexplicably avoided invoking national security concerns. Whether this was a legal miscalculation or a deliberate effort to avoid dragging central agencies into court remains unclear—but the consequence was significant. The High Court had no reason to view the matter as anything more than a commercial dispute.

Next in line is the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) and the Bureau of Civil Aviation Security (BCAS). These are the regulatory pillars responsible for enforcing and communicating security clearance decisions. In Delhi, BCAS was active and assertive in defending its move to revoke Çelebi’s clearance. But in Mumbai, the same agencies were silent spectators, failing to even file an affidavit in support of MIAL. This absence of coordination—or perhaps unwillingness to intervene—allowed Çelebi to frame its own narrative without contest.

Even the government’s legal machinery, which acted decisively in Delhi by involving the Solicitor General and submitting intelligence in a sealed cover, failed to act with similar urgency in Mumbai. No senior legal representative appeared on behalf of the Union to present the national perspective. The contrast is glaring—and damning. It raises troubling questions about why the same government, dealing with the same company, could present two completely different cases in two different cities.

What could have been a unified security position across jurisdictions turned into a fragmented mess, driven not by judicial inconsistency but by executive inaction and strategic sloppiness.

Legal Myopia or Executive Evasion?

The Çelebi case exposes not just a lapse in legal coordination but a deeper structural problem: how the Indian state approaches the intersection of law, commerce, and national security. Was it judicial myopia that led to a seemingly lenient outcome in Mumbai? Or was it executive evasion—the failure of central and airport authorities to present the case with clarity and urgency?

The truth is more uncomfortable: it was both.

On the one hand, the judiciary continues to rely heavily on what is presented to it, particularly in commercial disputes. Unless security concerns are raised explicitly—through affidavits, sealed submissions, or legal arguments—judges are unlikely to look beyond procedural fairness and due process. Courts cannot be expected to behave like intelligence analysts. That’s not their role, and they are bound by the limitations of evidence presented.

On the other hand, the executive apparatus treated this like two different cases—one worth fighting in Delhi, and one worth outsourcing to airport management in Mumbai. The central government did not even attempt to maintain consistency in its legal posture. Worse, it failed to ensure that its own agencies communicated with each other and presented a unified front. In an era where aviation infrastructure is increasingly seen as a frontline in national defense, this kind of bureaucratic disconnect is not just embarrassing—it’s dangerous.

This also reignites debate over the “sealed cover jurisprudence” practice. While controversial for its lack of transparency, it exists precisely to allow courts to consider national security evidence without compromising intelligence protocols. In Delhi, it was used effectively—perhaps too uncritically—but at least it served its purpose. In Mumbai, the tool wasn’t used at all.

The system didn’t just malfunction. It ignored its own alarms.

The Broader Implications?

The implications of this fractured legal approach go far beyond the fate of one ground handling firm. At a fundamental level, it undermines India’s credibility in enforcing national security protocols consistently. If a company can be deemed a potential security threat in one city and continue unimpeded in another—based on how the case is presented—what message does that send to foreign contractors operating in critical infrastructure sectors?

It also opens a dangerous precedent: security clearance revocations may now be treated as bureaucratic hurdles instead of national safeguards, especially if the concerned agencies fail to follow through in all relevant jurisdictions. This inconsistency can be exploited by well-resourced firms with strong legal teams and transnational ties. The Çelebi case, for all its legal sophistication, risks becoming a template for how to outmaneuver India’s fragmented security enforcement regime.

Moreover, the judicial inconsistency—though not entirely the fault of the courts—erodes public confidence in national institutions. For citizens, it is baffling to watch the Delhi High Court defer to national security concerns while the Bombay High Court hears none. It creates the illusion of a country where security depends on the courtroom ZIP code. In strategic sectors like aviation, this is not just a perception problem—it’s a real risk.

At a time when India is investing heavily in modernizing its airports, inviting global investors, and positioning itself as a safe, sovereign power, such lapses threaten to turn critical infrastructure into soft targets—not because of enemy action, but because of our own institutional dissonance.

Conclusion?

This contradiction between Delhi and Mumbai High Courts is not just a legal curiosity—it is a flashing red light for India’s national security apparatus. The Çelebi case reveals a system where the right hand of the state claims a threat while the left hand signs off on business as usual. Such dysfunction doesn’t just undermine judicial integrity or bureaucratic coherence—it invites exploitation, endangers aviation safety, and signals to foreign players that India’s security red lines are flexible, negotiable, and worse, forgettable.

It is imperative that the Ministry of Civil Aviation, BCAS, and the Prime Minister’s Office take note of this disjointed handling and issue clear protocols. If a vendor is flagged as a security concern in one state, that decision must carry weight across the country—through urgent central coordination, not through passive silence.

The judiciary, too, must evolve mechanisms to ensure uniform scrutiny of security-linked cases, even in commercial contexts. Perhaps a fast-track bench for infrastructure security issues is needed—one that can assess both legal rights and strategic implications without waiting for someone to mention the obvious.

Because when Delhi sees a threat and Mumbai sees a tender, we’re not just dealing with a contradiction. We’re flying blind—at 30,000 feet, with the cargo door wide open.