Breaking Down The News: Who Really Pays for “Free” UPI Transactions?

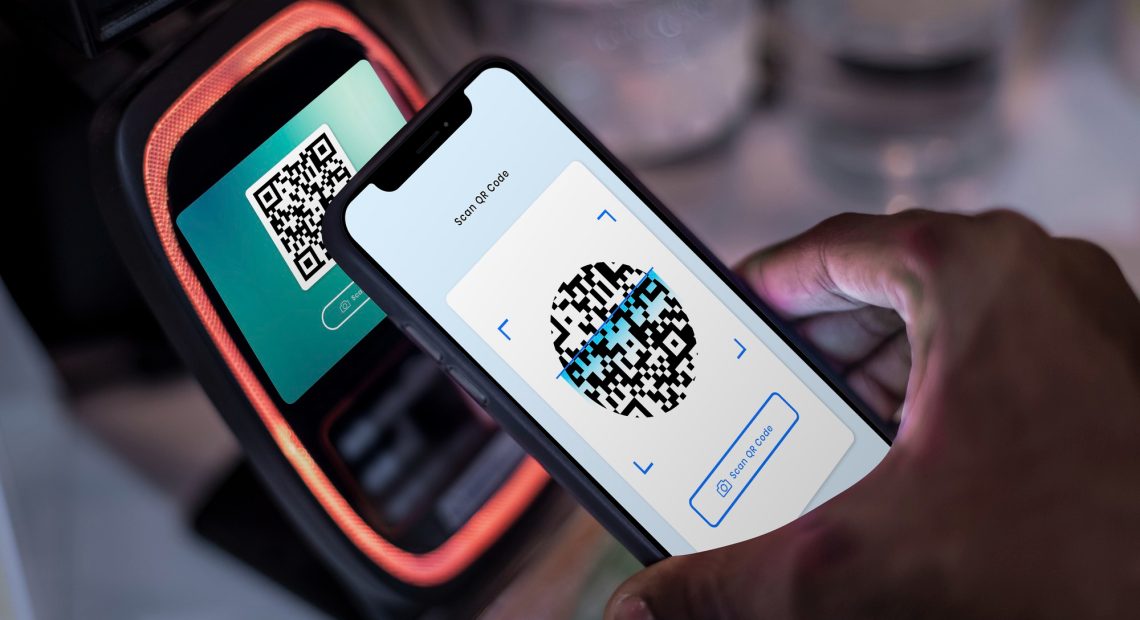

The Unified Payments Interface (UPI) has transformed how India pays. With just a mobile number or a simple scan, millions of Indians transfer money instantly — and at zero cost to themselves. But while users celebrate the seamlessness and the “free” nature of UPI, the question few ask is: who’s really footing the bill?

Behind every UPI transaction is a complex and expensive system — and someone is paying to keep it running.

The Unified Payments Interface (UPI) system operates through a finely interconnected ecosystem. At the center is the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), which runs the UPI switch, ensuring transactions flow smoothly between banks and payment apps. Then come the banks themselves — the issuers (where the money is debited from) and acquirers (where the money is credited). Payment Service Providers (PSPs) like Google Pay, PhonePe, and Paytm offer the user interface, while merchants enable acceptance at the point of sale.

It’s a well-oiled machine, but keeping it running isn’t cheap.

Despite no charges for users, the UPI ecosystem bears significant costs. Banks shoulder the largest burden, roughly 50–60% of the operational costs. They invest heavily in core banking systems, transaction security, fraud detection, customer support, and backend reconciliation. PSPs and third-party app providers absorb about 20–30% of the costs, managing mobile apps, customer engagement, and backend technical infrastructure. NPCI, operating the UPI switch itself, accounts for about 10–15% of the total running costs, ensuring 24×7 availability, server capacity upgrades, and cybersecurity protocols. Merchants too bear a small portion (around 5–10%) by setting up payment infrastructure and handling transaction-related customer issues.

So, while your ₹100 chai payment may look effortless, there’s a complex, expensive ballet happening backstage to make it happen in real-time.

In 2020, the Indian government mandated zero Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) for UPI and RuPay card transactions. Previously, merchants used to pay a tiny percentage of each transaction as fees — much like they still do for credit card payments. But with zero MDR, neither merchants nor consumers pay anything for using UPI.

This decision gave a massive boost to digital payments but eliminated a crucial revenue source for banks and PSPs. It turned UPI into a public good, but one without a clear funding model. Private entities are now essentially running critical national infrastructure at their own expense.

Recognizing this strain, the government introduced incentive schemes. For FY2023–24, about ₹3,000 crore was allocated to compensate banks and PSPs. However, this covers only a fraction of the total estimated ₹12,000 crore operational costs. In reality, stakeholders are absorbing a shortfall of around ₹9,000 crore every year — an unsustainable model in the long run.

While standard UPI payments remain free for users and merchants, a minor fee now applies to transactions made via Prepaid Payment Instruments (PPIs) like wallets (PhonePe Wallet, Paytm Wallet, etc.). If a PPI-based UPI payment exceeds ₹2,000, merchants pay an interchange fee of up to 1.1%. However, this fee structure is designed to impact high-value merchant payments, not everyday peer-to-peer transactions. For the average user, UPI remains entirely free.

This measure offers a partial revenue stream for PSPs and banks, but it’s a mere patch compared to the broader financial demands of sustaining UPI.

UPI’s astounding success — processing over 11 billion transactions a month — is now becoming its challenge. As volumes grow exponentially, so do computing, server, and cybersecurity costs. System outages in March and April 2025 exposed how fragile the infrastructure can become under stress if upgrades don’t keep pace.

To ensure UPI’s sustainability without disrupting its inclusivity, India may soon face hard choices:

Should nominal fees be introduced for certain kinds of UPI transactions?

Should the government increase direct subsidies for ecosystem players?

Should stakeholders be allowed to innovate business models, such as value-added services, to earn revenue?

UPI has rightfully earned its place as the pride of India’s digital economy. But behind every “free” transaction is a hidden invoice that someone — banks, payment providers, the government — continues to pay. As India marches toward even greater digital adoption, it must ensure that the financial plumbing supporting this revolution is not left to run dry.

In the world of digital payments, someone always foots the bill — and right now, it’s everyone but you.